Looking for Charlie Russell

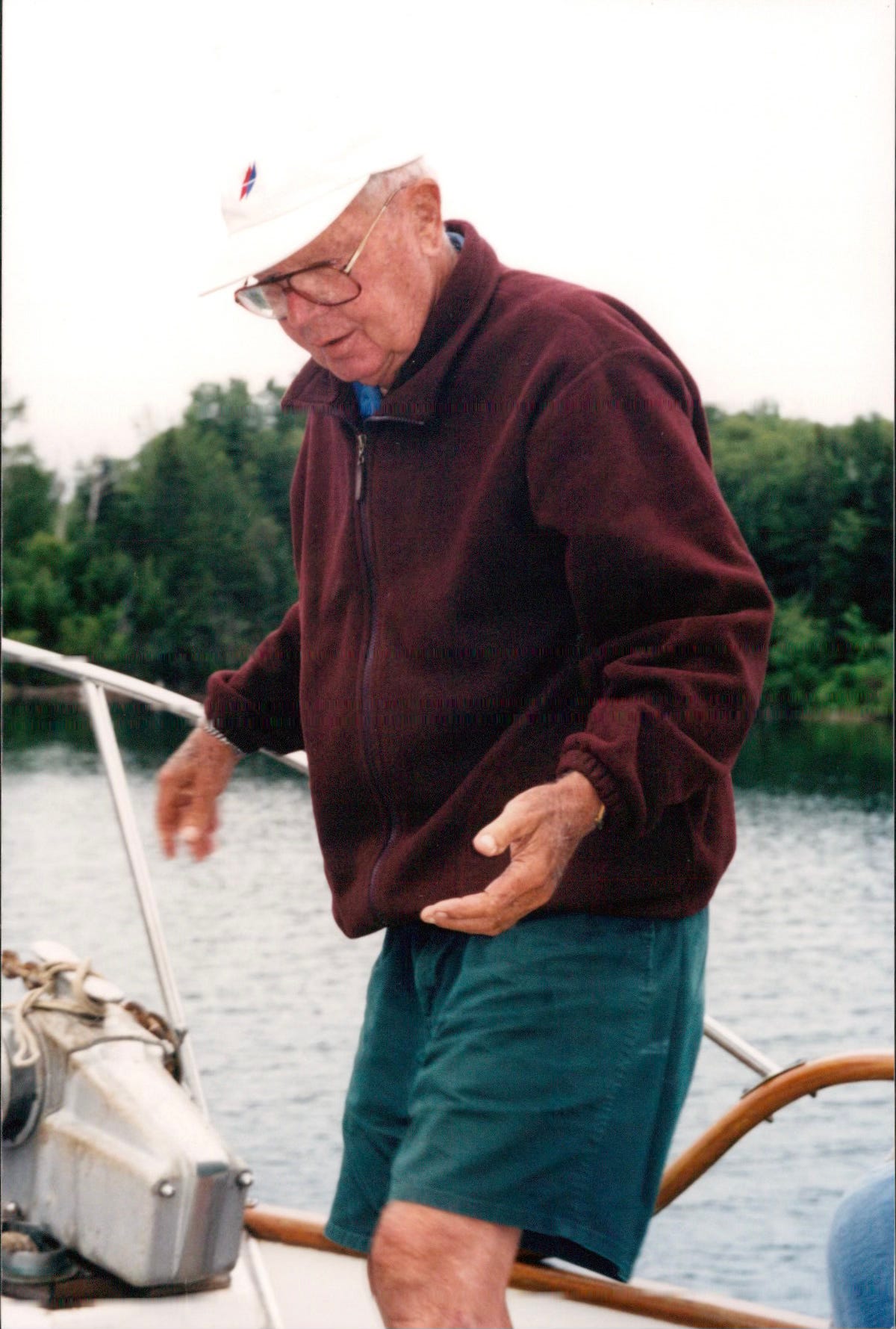

I wrote this essay back in the 90’s, before we had our house in Georgetown. I was reminded of it today when we took the afternoon off from our labors (and it’s 90* here) and drove over to Hallowell for lunch. Saw roads going to unknown places, none of which Sam would be tempted to take, even if it were cooler. Above is Dad, looking here at a recalcitrant outboard motor,,

From our summer rental, Medomak Cottage, I jog down Back Cove Road: past the clammers digging in the tidal flats of Pitcher’s Cove and conversing loudly over the beat of AM radio; past the mastless old Friendship Sloop shrouded with plastic sheeting on a cradle in the meadow; past the lazing junkyard dogs on chains in the dirt yard of the house on the corner of Deaver Road. I turn on Deaver, towards Jones’s Neck, and on the way up the hill I flush a flock of partridge, who startle out of the ditch off into the trees.

At the bottom of the hill on the left is an old fire road I’ve never taken. All August, two tires have blocked the grassy track – meaning, I figure, that there may be an unoccupied cottage up the road, or at least that somebody’s bought the land and doesn’t want visitors. But now it’s after Labor Day and the tires are gone. An invitation, if I ever saw one! I veer off into the woods.

The track is overgrown, but passable. I brush past low branches of hemlock, hop over evergreen seedlings in the path. The footing is soft and spongy, layers and layers of fallen needles and grey-blue moss cushioning my steps. September sun filters through the second growth, dappling the forest floor, intermittently warming my face and arms.

The track winds uphill between small outcroppings of granite. At the top of a rise there’s a widening, and a small old graveyard. The headstones, maybe three dozen, are all askew, chipped, mossy, some of them fallen over. Most of the inscriptions are too worn and obscure to read but I can trace a couple – Asa Hoffes, 1792—1856. Phineas Lash, 1803-1887. His Beloved Wife Susannah, 1818-1880. Hoffses and Lashes abound in Waldoboro and Friendship; plainly, they have abounded here for a long time. I pull one small stone erect. Maria, it simply says.

Below the graveyard lies a field, and a vegetable garden with rows of corn and tomato plants visible, a white farmhouse. I can see Back Cove Road, the meadows beyond, and Back Cove itself, in the distance. For several summers I’ve been hunting around the woods on Jones’s Neck for a cut-through between Deaver and Back Cove Roads. Now I’ve found it.

******

My childhood was filled with expeditions, real and imaginary. In a way we were two families of children: Anne, Win, and Ben, three children in three years, a gap of five years, and then Ellen and Susie. However many of us there were, my parents would gather us together on a Saturday or Sunday, together with a picnic and other paraphernalia, and we’d set out for somewhere.

In the summer we’d go day sailing or cruising overnight in one of our succession of sailboats: Surprise, Amantha, Seguin, Sequence. In the fall or spring we might load one of the dinghies onto the trailer and head inland to a lake or river launching place. Or we’d drive to Bradbury Mountain or Cathedral Ledges and climb, we kids alternately racing and lagging, yodeling and whining, to the view, to the spot where we could finally eat our tuna sandwiches and potato chips, down the double pack of Fig Newtons.

Dad was the animating spirit of these adventures. He’d worked hard all week, he hadn’t seen much of us except while he read to us each evening as we ate our supper; read to us from Swallows and Amazons, or one of the Doctor Dolittle books, or King Solomon’s Mines; took us on our imaginary adventures. I recognize now that he read to us as a form of crowd control as well as for entertainment and instruction. That system worked splendidly, but on weekends, on our actual travels, he needed to devise other methods for amusing us, for challenging us, for distracting us from our main occupation, which was quarreling. My mother, an only child, once remarked, “I had a so many children because I didn’t want you to be lonely. And then, all you did was fight!” And when we were not bellicose we were most often slothful and timorous.

My father did not suffer fools gladly, nor did he suffer querulous or lackluster children. As we drove, as we navigated the Royal River, as we climbed toward Diana’s Baths, we sang songs, we played games –standard games like Twenty Questions and games of our own devising. One was the Question Game, in which we tried to stump one another with hard choices between personal preferences: Win, which would Anne rather do, meet Sargent Preston in person, or quit piano lessons? Through such diversions would Dad challenge us to rise above our baser instincts, our childishness and our longuers.

We did, as I’ve said, visit some well—known scenic spots. But Dad’s preferred destinations were less traveled, our private discoveries: the wide muddy creek off Sligo Road where we could launch the outboard and explore marshy highways and byways, pass box turtles sunning themselves on half submerged logs, or the brambly headland of Jewel Island, where our sneakers would crunch on mussel shells that gulls had dropped to crack open on the rocks.

And even at the populous tourist spots, toward the end of the day, Dad would lead us off the main trail, “off the beaten track” — he would urge us – onto some inviting private road or path. My father was drawn to Private Property signs as a bee to the flower. “Come on,” he’d insist, “let’s see what’s up this way.”

“But it says, Keep Out,” someone – my mother, at first, others of us as we learned to read – would protest. “It says, No Trespassing,” or “Beware of Dog.”“There must be something good up here they don’t want anyone to discover,” Dad would explain. “Let’s find out.”

“But what if they see us?” one of us would whine. “What are we going to tell them? What are we doing on Private Property?”“We’ll tell them,” Dad would answer, triumphantly, every time,“we’ll tell them we’re looking for Charlie Russell!”

*****

I was a very different kind of parent: personality, circumstances, context. My husband left me when I was pregnant, took off with our upstairs tenant, never to return. I was the single mother of a single daughter, Lizzie, and for all of Lizzie’s childhood, until she was 18 and in college, we were a unit of two. And during those years of her childhood I was making my way through graduate school in English Literature, writing a dissertation and teaching composition and literature to engineers, then making my way through seminary and ordination in the Episcopal Church, then serving as rector of a parish.

So for all those years I was working, going to school and working, working two or more jobs at once, managing on little money, Not to mention managing, or mismanaging, a long series of disastrous love affairs. I often spent my Saturday mornings in bed, reading The Poetry of George Herbert, Understanding the Old Testament, The Birth of the Messiah. Sunday mornings were devoted to church. And there were always, until I finally left teaching for full—time parish ministry, always Freshman Composition papers to grade. Little opportunity for daylong expeditions of the kind I’d enjoyed, or endured, as a child.

But Lizzie and I did have our adventures. She rode in a plastic seat on the back of my bike, wearing a yellow plastic hard hat, and later we rode our bikes together, along miles of private roads in Boston’s western suburbs. We picked milkweed in other people’s meadows and lilies of the valley in other people’s woods.

“What if we get caught?” Lizzie used to wonder nervously.

“We’re looking for Charlie Russell, we’ll tell them.”

*****

“Who is Charlie Russell?” we would demand of our father, lagging behind as he strode confidently, purposefully, along on someone else’s property.

“You know, Charlie Russell, my college roommate!” he would answer.

We’d heard many stories about Dad’s college roommates. The time they bought an old piano and burned it piece by piece in the fireplace in Horton Hall, the time Heffron, trying to sleep after he’d pulled an all-nighter studying for a final exam, shot his alarm clock with a 22. And we’d met them, Bob Page who’d had a medical tour of duty in Rangoon and would chant loudly in Burmese after he’d had a martini, Turk Orr, who owned a cattle ranch in Montana and who wore a cowboy hat and boots in our house! in Maine! And John Heffron, my godfather, who liked to help Dad try to shoot the rats who lived in the cellar and under the garage. But we had not met Charlie Russell.

“Charlie Russell, ‘my college roommate,’” Dad would say. He is a man who employed irony with great and cheerful frequency, and soon we learned to recognize the pitch of the inverted commas by which he separated himself from many of his own pronouncements. We came to understand that Charlie Russell was not, never had been, Dad’s college roommate. And then we came to understand that there was no Charlie Russell, at least, no Charlie Russell my father had ever known.

“Why not use a real name, a real roommate?” we wondered.

“Because who knows, the guy who owns this place might actually know Heffron.

And then we’d been in real trouble.”

What kind of reasoning was this? What was the likelihood that the random owner of a small island in Casco Bay or some acres of woods in Raymond or Bridgeton would know one of the actual and far-flung graduates of Princeton’s Class of ’43? How small is the world?

*******

One summer when Lizzie was small we went cruising with Mum and Dad in their big catboat, Counterpoint, on the St. John River in New Brunswick. The landscape was reminiscent of an 18th Century French painting – soft hilly meadows rolling down to the wide river’s banks, occasional ancient shade trees. Deeply wooded shady covers, and the distant sound of loon laughter. A remote area, not frequented by yachtsmen.

One day, as we were anchoring in a secluded inlet for lunch, a Boston whaler approached and circled Counterpoint several times. The helmsman put his outboard in neutral, stood up, and waved. “Didn’t you go to Choate?” he yelled at Dad.

The world can be very small indeed, it seems.

********

Lizzie developed her own spirit of trespass, confined at first to our small neighborhood in Belmont. In the summer she’d bring me home straggly fistfuls of mint for my iced tea, mint which, judging from her appearance, she’d procured by crawling under somebody’s fence. She’d never tell me where she found it; her theory was that if I didn’t know, I couldn’t get in trouble.

“If they catch me, I’ll tell them I’m hiding from the Tinkers,” she would reassure me.The Tinkers were three indistinguishable brothers who patrolled our street in ramshackle soapbox cars—they could make anything run, fix anything, it seemed, from toddlerhood on, and they were in fact a benign and sunny bunch who acted as a protectorate to Lizzie, the smallest kid on the block. But her fiction that they were her perpetual pursuers, her version of the Charlie Russell story, justified her to herself.

In second grade Lizzie made a new friend, Stephanie, a plump contemplative child who played the violin badly but devotedly and who cherished a large collection of Ginnie dolls. Stephanie’s father had grown up in Brooklyn, a Red Diaper baby, and he and her mother had met at the Columbia strike in 1967. Their daughter, whose sensibility seemed firmly lodged in the 1950’s, like her Ginnie dolls and indeed like Belmont, our town, itself — Stephanie was to them an anomaly, a genetic quirk. Stephanie, this offspring of true, honest-to-God lefties, doubtless on file with the FBI, Stephanie believed that even to read a No Trespassing sign was to commit an illegal act.

“Come on, Stephanie!” Lizzie would yell, as she and I slipped through a hole in the chain link fence around Fresh Pond to take a quick, illegal dip in the reservoir. “Enjoy nature!” But Stephanie would hang back, clutching a Ginnie doll, ostentatiously reading a book, trying to avoid guilt by association.

********

Across Deaver Road from the old fire road lading up to the cemetery is another track through the forest. This one leads by Harlan Creamer’s right-of-way to Pitcher’s

Cove. Leads back a few hundred yards to a small grey shingle cabin number in stick-on reflective digits, # 175.

I climb the four steps up to a shallow porch facing the cove, which can be glimpsed through the tall dense evergreens. On the other end of the porch there’s a ramp. How, I wonder, would you get a wheelchair through these woods, over the thick exposed tree roots and around the small boulders?

I peer through the dirty, cob-webby front window with its grey-white fraying fiberglass drape. Inside the long narrow single room I can make out a fuse box, a gas cylinder and a two-ring gas cooker, an egg crate foam rubber mattress rolled up inside a plastic garbage bag on top of a plywood platform single bed, and a small fridge. One corner is curtained off by a red sheet patterned with small blue and white sailboats – concealing a toilet?

This little deserted camp is paneled in imitation birch, the floor carpeted in gold shag. In these decorative details it resembles the house in Davis Square, Somerville where I lived with Lizzie’s father in the early 70’s, before she was born. We had that same faux birch on our walls, we had a orange shag rug, and we were so pleased with our taste then, so stylish!

Near the window I’m peering through stands an aluminum-legged table, its red linoleum top illustrated in nautical knots —sheet bend, I can see, bowline on a bight. On the table are piled three books, The Supermarket Cookbook, hardbacked and old, The Rangeland Avenger, by Max Brand, also hardcover, and a big old Larousse Encyclopedia of Astronomy. On the bottom of the pile is a copy of Sail Magazine, still shiny, pages not yet curled by moisture. Who’s been here, and when?

I proceed through the woods. One morning, my husband Sam and I tramped through here with a realtor who was trying to sell us a waterfront lot on the Cove with a view of a rock piled with Harlan Creamer’s lobster traps. The realtor told us that the whole of Pitcher’s Point belongs to one family trust—the entire small wooded peninsula with the exception of the plot he wanted us to buy.

Does someone from the family come to stay in the little grey cabin, #175? No traces of habitation in the summers I’ve been poking around here. I circumnavigate the Point, bushwhacking through the second growth and blowdown, treading the paths padded with so many hues and varieties of moss. Plenty of mushrooms and toadstools —small red-orange buttons, big black ones inverted, like chalices, and the garish yellow fungus I’ve learned is named “chicken of the land.”

Eventually I come out by the small pond, where I disturb a Great Blue picking in the shallows, a black turtle sunning on a rock. And here’s the other cabin on the property – the red shingled one. The roof over the stoop is covered with moss and pineneedles, and the stoop itself holds a pile of animal scat —raccoon, probably.

Out front is an old red wooden picnic table, splintered and sagging. When I first found this place, three years ago, a shiny new spatula lay on that table. It’s gone, now.

This cabin has a real stove and a fridge, but no other signs of domestic life in the main room except the white curtains embroidered in cross-stitch which hang limply in the windows. Someone started to insulate the tiny room on the east end but abandoned that effort; the pink and silver insulation hangs loosely now and the windows are broken.

On the ground by the stoop lies a white plastic dishpan filled with dirty rainwater. A small rubber face peers up at me through the algae. A diminutive mask of a Flintstone or one of the Addams family? I poke it to turn it over. It’s a finger puppet.

*********

One summer we took a rental right down in Friendship Harbor. I had suffered a stress fracture in my left foot, which made running impossible. Sam was finishing work on the little sloop he’d been building, Minerva, and spent his days in my brother—in—law J.V.’s workshop and back yard on Finntown Road in Waldoboro, painting, varnishing, and attaching rigging hardware. So I had time to myself when my exercise habits were curtailed – a challenging combination of circumstances.

Every morning I’d walk up the hill from the harbor and take a dirt road down past a couple of newish houses and some undeveloped plots. At the bottom of the road I found an overgrown two-lane track.

The first time I took this route I followed the track –no mean feat, it was fiercely overgrown with brambles – to its destination: something that had once been a clearing but was now a mess of saplings and high weedy bushes and waist-high tall grass. I pushed through to a house that stood in the middle of all this wilderness: a kind of house, a pre-fab, pale yellow vinyl- sided building with an ornate and cheesy decorative door and two small windows facing the ‘driveway.’

I was walking around the side of the house when I became aware, in my peripheral vision, of a dark shape above me. I looked up, and saw an old desiccated wasps’ nest attached to the eaves, strips of grey paper hanging raggedly from it. I found this, somehow, a grotesque sight. I couldn’t recall ever seeing a wasps’ nest on a house, or perhaps what spooked me was its obvious age –—it had been built, inhabited, and abandoned, and no one had disturbed it or, presumably, been disturbed by it in all that time. It seemed like a curse.

Disconcerted by the nest, I continued around to the front of the house to discover another thicketed yard and a tranquil view of a small inlet. White pines grew tall on the banks, and I could see a Great Blue heron perched on a branch.

The house had a shallow concrete ‘porch’ with a couple of cheap and puny columns supporting an aluminum awning. Even beyond the ugly strangeness of the whole set-up, something seemed off kilter. It took me a couple of minutes to figure out what: there were no windows in the front of the house. No view of the water view!

I walked home slowly, pondering these things in my heart. When I reported my adventures to Sam, he said, “I don’t think you should go back there.” Sam is a resolute anti- trespasser.

When I retraced my route the next day, I noticed a small hand-painted sign that had been nailed to a spruce tree at the head of the track. The Brown’s, it said, with that characteristic abuse of the apostrophe. And the next day, it appeared that someone had gone through with a heavy—duty mower – the tall grass and brambles on the track had been cut down and a narrow swath cleared around the house. The weedy debris still lay all about.

I described the odd set-up — a deserted pre-fab house with no front windows in a prime waterfront location—to my sister and brother-in–law. “You know,” J.V. said, “there used to be talk of drugs coming in over somewhere on Bradford Point.” Rumor, myth, or local crime wave? There’s a not-so-friendly feud between Friendship and neighboring Waldoboro, competition over the setting of lobster traps, the obtaining of permits. Was this talk part of that rivalry?

“I don’t think you should go back there, “ said J.V.

The following day, I found a rusty chain, held up by two newly installed galvanized iron pipes, blocking the entrance to the recently mowed track. I stepped over it and went down to the house to investigate. The mower had been back; some of the front yard was now cleared. The wasps’ nest still clung, ominous, on the eaves, and the house itself seemed unchanged.

Liz came up to Friendship for a visit, and I took her to view my discovery. As we approached the chained driveway, I saw that a No Trespassing sign had been nailed to the tree underneath The Brown’s. I explained the developments to the property since I had been visiting.

“Have you ever seen anyone?” she asked.

“Nope.”

I showed her around the house, the wasps’ nest, the windowless view of the quiet estuary. “Man,” she said, “this is totally creepy. Why do you keep coming here?”

“Well, I can’t run. I’m on a short leash,” I explained.

“Mom, you are not to come back any more,” my daughter told me.

Liz worries about me—I know she does. Worries about me more than she needs to, I think, but never mind. I didn’t want to cause extra anxiety by provoking an encounter with members of a mid-coast drug-running operation. Or whatever.

So I didn’t go back, and before long we moved to Medomak Cottage and I began my explorations along Back Cove Road. But next summer I’d like to check up on what’s happening down on Bradford Point. . .

What’s the allure? Sam can’t understand it: the violation of other people’s privacy, the risk of discovery, encounter, confrontation, rebuke, humiliation. The possibility of a hostile dog —well, there are plenty of those to contend with jogging on a public road. “I don’t like going onto other people’s property, “ he tells me, fussily, nor does he like side trips, bushwhacking, or uncertain destinations. He won’t accompany me on these expeditions.

I had to nag and wheedle to convince him to come with me for a land view of something we’d often admired while sailing Minerva – a very handsome, sturdily built, long wooden pier with no float attached. And no house in sight. Whose dock was this?

I had found the shore approach to this desirable and unused dock by way of a series of fire roads on Martin Point, and I’d found something else as well. I’d come up a small steepish hill, which opened out, into a clearing of granite and blueberry and juniper bushes. At the top of the clearing stood a square, two-story, very solidly constructed log cabin with a wide wrap-around porch.

I stepped onto the porch and peered through a window. The house was fully furnished in summer cottage style, with faded chintz –covered cushions, brightly enamel-painted wooden tables and straight chairs, bookshelves filled with old hardback novels, white cotton curtains trimmed in ball fringe. A huge stone fireplace dominated the one big first- floor room.

The green board door was locked and bolted. Cobwebs festooned the corners of the porch roof. The place hadn’t been entered for several years, I reckoned.

Quite a contrast to a pre-fab heroin drop decorated with a disused wasps’ nest! Here was a much classier version of isolated summer living. The location must have had a spectacular view of Muscongus Bay— must have had, once, because second-growth evergreens have now grown up all around the clearing. And the bizarre, the inexplicable thing about this house was that there was no road to it. I’d approached from the south by a track no more than two feet wide, and another narrow footpath led away to the north. No road, no sign that there ever had been a road. How had the house been built? How had the inhabitants brought in supplies? Did the floatless dock below somewhere, out of view, belong with this property?

I wanted Sam to consider this anomaly, these questions. He’s a scientist, he’s a builder and a fixer and a noticer; he might have some answers.

So when he agreed, reluctantly, to come with me through the woods one day to have a look at the dock he coveted, I planned to take him by the log cabin on the way. We ran up and down the old trails, retracing our steps more than once to branch off in different directions. But I could not find the right way to the cabin, and Sam grew tired of trying. He was impatient to go sailing.

So the puzzle remains. Well, there’s always next summer. . .

What’s the allure? These serendipitous discoveries, these tantalizing mysteries. How does a substantial house appear on a hill with no detectable trace of a road? Who was watching my exploration of the hypothetical drug -drop property, warning me off, day by day, with advisories incrementally less subtle? Who wheels up the ramp to the camp at # 175, sits at the small red table reading The Rangeland Avenger? Where did the Flintstone finger puppet come from, and where has the shiny spatula gone?

And there’s the possibility, the slight risk of being caught out, challenged, rebuked. That’s what stops Sam, I’m sure; that and a intrinsic respect for private property may give him pause. But the private property I’m drawn to, incorrigibly, is mostly deserted or abandoned. People inhabited these eccentric little buildings and furnished them with clues to their pastimes, their interests, innocent or outlawed. I’m drawn to spying on their artifacts, to speculating. Trespasser as social anthropologist.

And I cherish the solitude. I can walk the soft, needle-cushioned, hushed paths of Pitcher’s Point week in and week out and never meet a soul. I can run or walk, peer and poke about, digress where I will. I’m alone here, detecting, exploring, discovering. I’m getting my daily exercise, I’m on my own. No one knows where I am, and no one is looking for me. For this stretch of time I’m not responsible to anyone, for anything. In fact, I’m irresponsible, I’m trespassing.

And I love the places. If love determined ownership —which, of course, for better and for worse it does not—if love determined ownership, Pitcher’s Point would be mine. I trace and retrace my steps to the small pond by the red cabin until I’ve made the way my own. I may find that log cabin on Martin’s Point again before anyone else lays eyes on it. No one else seems to travel these faint, overgrown trails, fight through these thorny brambles, clamber over these fallen, decaying logs. Who else cares the way I do, notices as much as I do? Who else courts reproach, hostility, expulsion on a daily basis just to be here? Surely these places, spiritually, belong to me?

I’m a good citizen, I believe. I’m a priest, I run a small church, I do my best to be “a holy example” to my people. I’ve been a college professor, I’ve raised a daughter single-handed, and I’ve even become a pretty good stepmother. I lead a law-abiding middle-class life, filled with its share of conformity and conventional good works.

But I’ve also walked on the edges of things, the outskirts of the acceptable—those two young marriages and divorces, those ideas the church isn’t always quite ready for. Treading forbidden ground –—I may not be comfortable there, exactly, — but the territory’s familiar. I know that slightly off-guard, slightly defensive posture thoroughly. I know the exhilaration of the unexpected, and the satisfaction ——indeed, the thrilled gratification —of slugging through some thankless stretch of bureaucratic or ideological or emotional underbrush to emerge in an unfamiliar clearing with a new and unanticipated view. A revelation.

I’ve only ever been confronted once, and that, recently. I’d run across the narrow isthmus at Jones’s Neck onto the island housing a family compound of big old white homes. We see them when we’re sailing in Minerva — the long awninged decks with their views of Broad Cove and Back Cove, Locust and Haystack Islands, the volleyball net, the dogs racing down the sloping lawns. I wanted to see the set-up from the land side.

I ran up the road through the woods till I could see the first house but it was plain, even to me, that I couldn’t go closer without being conspicuous, intrusive. As I was retreating I heard a vehicle approaching from behind, and I moved aside and stopped to let it pass.

A big green SUV with Rhode Island plates stopped beside me and the driver’s window descended, automatically, 1/3 of the way. “This is a private road,” he told me, pointing at Private Property, No Trespassing, and Posted signs nailed to the trees nearby.

“Oh,” I said, in a startled voice, “Sorry. Sorry, I was looking for Charlie Russell. I guess he’s not here.”

He eyed me for a moment. We were both, and equally, I imagine remorseless. He pushed a button, his window ascended, and off he drove.

“That’ll teach you,” Sam observed later, when I told him.

Teach me what? After all, I pray every day, week in and week out, “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Why pray the prayer, if I don’t walk the walk?

A For Sale sign gets posted by a yellow cottage on Deaver Road, right beyond the entrance to the camp at #175, right where Harlan Creamer has his right of way. I prowl around and squint through the windows, and while the place doesn’t look like much, it has a garage and dock and a view – that same rock piled high with Harlan’s traps and beyond that, Pitcher’s Cove. And so when we return from vacation I call the owner, or at least the seller, a guy named Howie, a talker.

Howie tells me all the virtues of the place and the price, which seems outlandish and anyway the recession is just kicking in so why buy just now? Howie tells me about Harlan’s right of way and about the last resident who died there at ninety-nine, and then he tells me that the family trust has sold the whole of Pitcher’s Point to a developer from Augusta.

“Thirteen house lots!” he exclaims. “Only 13!”

“Only 13?”

“Well, they were saying 25 at first. And these’ll be classy,” he told me. “It’ll be good.”

Good for whom, you jerk? But it’s not his fault, not exactly. Don’t shoot the messenger, Anne. Howie might have a house for us somewhere, sometime.

“Well, thanks for the info,” I tell him. I hang up the phone and sit in my office for awhile, staring out at the city street. No more # 175, no more red cabin. No more Great Blue in the small peaceful scummy pond.

I feel – well, never mind what I feel. What I feel is all too predictable, all too banal.

And then, after a while, gratitude. I’m glad I was there, glad I got to know that place, was privileged to scout out and share its secrets for awhile.

And then, that little tick of anticipation. Next summer I’ll have to find somewhere else to go hunting for Charlie.